Most people have misconceptions about how flight works, you don't have to understand the details of flight to fly but having a grasp of the basics helps.

As long as the wings are moving forward they will produce lift. Lift is one of the the forces on the glider. The others being drag (friction) and weight (gravity). Weight always pull the glider towards the ground, and drag always tries to slow the glider down.

The lift from the wings pushes the glider up and forward. This lift keeps the glider in the air; unfortunately, as the glider moves though the air, drag slows the glider down. To maintain a constant speed, the glider must therefore fly slightly ‘downhill’. Hence the glider slowly loses height over time. A typical training glider will have a glide ratio of 30:1 (it will lose one unit of height for every thirty it moves forward) while a high performance glider will have a glide ratio of 60:1 or more.

See also: Aerofoils and Wings

This video on the CUGC YouTube channel explains this.

Contents

Lift and Soaring

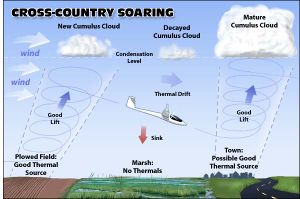

If you want to fly further than your glider’s glide ratio, you must then gain height. This is done by finding rising air, confusingly also called lift. The act of flying in lift is called soaring. While flying in lift, the glider is still going 'downhill' but as the air around it is rising, the glider gains height, like walking down an up escalator.

Thermal lift

See also: Introduction to Soaring#Thermals

The most common form of lift is thermals. Thermals are bubbles of air that are slightly warmer than the surrounding air; because of this, the bubbles rise. An experienced glider pilot can identify thermals and then fly within them. While in a thermal, the glider can gain height and therefore continue flying. Thermals vary in strength and the maximum height they rise to, but a typical good thermal in the UK could be rising at 400 ft/min (0.5 kph) to a height of 5,000 ft (1,500 m).[1]

Ridge lift

See also: Introduction to Soaring#Ridge (Hill) lift

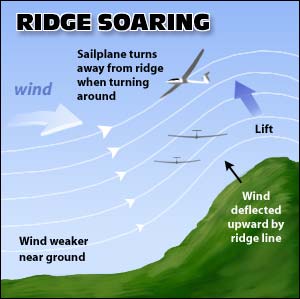

Ridge lift is created when a wind strikes a mountain ridge or cliff that is large and steep enough to deflect the wind upward. This creates and area of rising air, which when flown in allows the glider to gain height. Although the glider cannot go very high on ridge lift (up to about 2× the height of the ridge), it is very reliable so gliders can travel great distances by flying along long mountain ranges or hills.[1]

Wave lift

See also: Introduction to Soaring#Wave lift

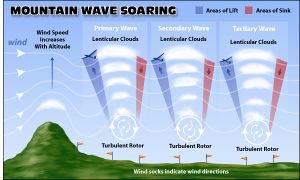

Wave lift comes from wind blowing over mountains and setting up standing waves. These create areas of rising and falling air which can go extremely high.[1]

Landing

See also: Field Landings

Eventually you will have to land; ideally, you land back at the airfield. However, experienced pilots may ‘land out’ in a farmer’s field. Once you are about 800 ft (250 m) above the ground, it is time to land. A typical landing starts with a circuit; this involves flying parallel to the airfield in the opposite direction to that which you wish to land and performing a series of turns so that you are at the correct height and in the correct position to perform the landing.

At the end of your circuit you should be at one end of the airfield at around 300 ft, you can then open the air brakes, which increase your rate of decent to bring the glider gently down to the ground. With practice, it is possible to bring the glider down in a small field with great precision.